By Karen Davis, PhD, President of United Poultry Concerns

Posted on One Green Planet April 30, 2014

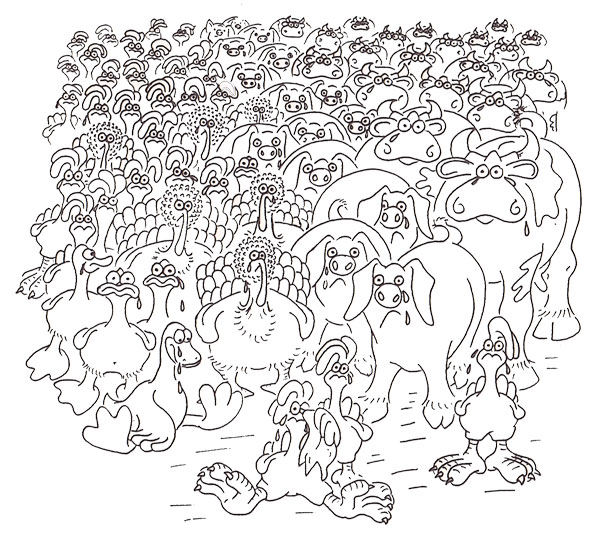

Illustration from Nature’s Chicken by Nigel Burroughs courtesy of United Poultry Concerns

Cattle, sheep, swine, asses, mules, and goats, along with chickens, geese, and turkeys all agreed enthusiastically to give their names back to the

people to whom – as they put it – they belonged.

– Ursula Le Guin, “She Unnames Them,” The New Yorker

“Please, never, ever, call me a battery hen. A hen in a battery cage is not a battery hen. I, Minny, am a proud descendant of the Red Jungle

Fowl.”

– Clare Druce, Minny’s Dream

A problem for animal advocates is the terminology of animal usage. Speaking for animals involves negotiating a terrain of verbal conventions that devalue

animals, starting with separating “animals” from “humans.”

Farmed animal advocates, especially, are beset by the language of agribusiness. Animals are depersonalized, even de-animalized, in farm-speak as

“broilers,” “layers,” “livestock,” “cattle,” “steers,” “veal,” “swine,”

“poultry,” “meat birds,” and the like. Putting these terms in quotation marks is one way of signaling that this particular cow, for

example, is more than just a “dairy” cow. At the same time, too many quotation marks add verbal clutter, so this problem, too, has to be

solved.

Recently an animal advocate challenged another advocate for using the word cow for an animal who was probably a

steer – a castrated bull in

a feedlot.

The issue was that “cow” normally denotes a female animal whereas bull or steer designates a male – one who is either sexually intact or

sexually altered. In my view, the word steer, though technically correct for a castrated bull, discourages empathy in people who are already emotionally

detached from “cattle” – another term that is drained of subjectivity and feeling.

We ended up agreeing that “cow,” being a kinder, warmer, more caring and relatable word than “steer,” is therefore appropriate for

both genders – even farmers sometimes use it that way. Regardless, the fact is that most people will never relate to an animal called a

“steer.”

If in certain circumstances we feel compelled to use the term “broiler” to distinguish chickens bred for meat, this term should never be used

as a noun but only as an adjective: Do not say “broilers.” Say broiler chickens. Don’t call hens used for egg-production

“layers” or “egg-layers” but rather laying hens. Don’t talk about raising “veal” or refer to a veal

calf’s prison as a “veal crate.” Instead say veal calves and veal calf crates. Make the animals visible.

As much as possible, simply say chickens, hens, cows, calves and pigs, and always avoid terms like “grass-fed beef,” “pasture-raised

eggs” and “pasture-raised chicken.” Only a live animal can be raised, not body parts and corpses. There’s a big difference

between “pasture-raised chicken” versus “pasture-raised chickens.” Likewise, a “chicken leg” is one thing, a

“chicken’s leg” is another.

Agribusiness: Owners or Guardians?

Responding to a United Poultry Concerns campaign alert urging the National Fire Protection Association to require the owners of farmed animals to install

smoke control systems in animal housing facilities, a reader sent me a “friendly reminder” that saying “owners of these animals”

reaffirms the animals’ status as property, not individuals with rights. Isn’t guardian the right word to use? I would say Yes in most

cases, but not in this one.

Given that victimization and violence are the essence of the relationship between agribusiness corporations and the animals they own, calling them

“guardians” would be a mockery of the animals and a mockery of the word guardian in the sense of responsible caregiver for a dependent fellow

creature or companion.

Each time we speak or write as animal advocates in the public sphere, we must choose our words carefully in our effort to get people to care about and want

to help the animals whose guardians we are, not only at the level of physical reality but in the realm of rhetoric – the art of persuasive discourse.

As Minny cries out to her rescuer in Minny’s Dream, being locked in a battery cage does NOT make her a “battery hen.” She is Minny . . .

Photo by Clare Druce courtesy of United Poultry Concerns