I first became involved with chickens when I lived on a small farm in Northern California. I was a lacto-ovo vegetarian and wanted eggs from

chickens who were humanely raised and allowed to live out their natural lives. My first chickens were purchased mail-order through the Sears

Catalogue. At the time I had no idea of the abuses in chicken hatcheries, and it

just didn’t occur to me how frightening it must be for chicks to travel in a dark box by mail. As I walked into the Post Office, I could

hear the soft peeping of those little chicks. . . .

The first day I found an egg in the nesting box was one of celebration. Here was a perfect egg, and no hen had suffered to produce it. Not yet.

. . .

As the chickens matured, their eggs got larger.

For several birds the eggs got so large they could no longer be laid with ease and the chickens strained for hours to pass the huge eggs. What

the catalogue hadn’t mentioned in extolling the little chickens who laid the big eggs was the problem of uterine prolapse. When

a small chicken pushes and strains, day after day, to expel big eggs, the uterus may eventually be pushed out through the vagina. It cannot be

put back easily because of infection. Further, the first egg produced would cause a reoccurrence of the prolapse. I called my veterinarian who

said nothing could be done but to euthanize the chicken humanely. And so my little flock got smaller.

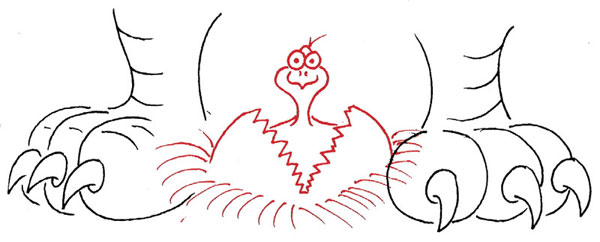

Eggs are best when left with mom to hatch.

Eggs are best when left with mom to hatch.

Spending the whole day roaming around and scratching

the ground are things chickens love doing best.

Spending the whole day roaming around and scratching

the ground are things chickens love doing best.

Another benefit of the White Leghorn, according to the Sears Catalogue, is that the maternal instinct has been bred out of the hens so they

don’t “go broody.” Going broody is the notion hens get to sit on eggs

and raise a family. During this time, hens stop laying. Needless to say, this tendency has no commercial value.

One of my hens seemed to be a throwback, however, and began spending all her time in the hen house, sitting on the nest. Since I had no

rooster,

the eggs weren’t fertile and her efforts would have proven futile had I not procured some fertile eggs from my neighbors and placed them

in the nesting box. Nineteen days later, I woke to see her out in the yard followed by five little red balls of fluff. She was an attentive

mother, teaching the chicks to scratch and all the best places to look for food. Soon the chicks were as large as their “mother,”

but they still gathered underneath her at night. It was so comical to see these large, gawky adolescent youngsters sticking out on all sides of

the little white hen.

|

As the chicks grew older they began sparring with one another, and it turned out that I’d gotten five roosters. My place was too small to

keep all five, since they each needed their own territory, so I began the near-impossible task of locating permanent, loving homes for my extra

roosters. Realizing that the production of eggs also involves the production of “excess” male chicks was the final nail in the

coffin of my lacto-ovo vegetarianism. I realized it is virtually impossible to produce truly cruelty-free eggs.

Jennifer Raymond is a member of

United Poultry Concerns and author of The Peaceful Palate: Fine Vegetarian Cuisine.

|

|